Girlie Techno

If an android believes that it is a human being, is it therefore a human being?

If a simulacrum believes that it is an authentic artefact, is it?

And what does it signify when the androids and the simulacra are all that remain of humanity and authenticity?

The expression Girlie Techno was’t invented by me, although I’d love to take credit for it. I saw it on a club flyer in 2009, and the phrase intrigued me, and then I saw it again on an in-store advertisement on a video display in Tower Records a week or so later. The expression was never, I don’t think, in wide circulation, although it was expressive enough for most people with a passing acquaintance in popular culture and popular music to be able to figure out what it meant. In brief, apart from being A Useful Catch-All Term For A Thing I Already Knew About, it was a short-lived and fairly tightly-defined subset of Electronic Pop Music from Japan featuring heavily-processed female vocals and music that pulled together the strands of the harder end of the House spectrum with bits ripped off, appropriated and re-interpreted from UK and German Progressive Rock from between about 1975 and 1980. It wasn’t built to last, and it didn’t last, but while it did, it was quite, quite lovely, utterly adorable, eccentric but accessible, irascible but warm-hearted and marked, in every sense of the word, the very end of what might be reasonably understood as ‘Idol Music’ up to that point.

There have been, of course, Idols since 2012. But no-one is convincing anybody – or even trying to convince anybody – that AKB48 et al are marketed at anybody who isn’t already predisposed to be a fan of AKB48. Because, obviously, I’m interested in how things are targeted, marketed and aimed at women, and what women are supposed to make of them, it leaves anything I might have to say about AKB48 et al completely moot and redundant, because that engagement doesn’t exist. Up until (let’s say) the falling-off in the broad popularity of Koda Kumi (in about 2009), it was reasonable to say that Idols were for Everybody. Some of them appealed more to girls than boys, and not necessarily the ones you’d think. Kumi, for instance, seems purpose made for male consumption, but it turned out that lots and lots of girls admired her good-natured assertiveness, her healthy BMI and her willingness to not so much ‘talk’ as ‘sound off as often and as loudly as possible’ about subjects that…weren’t exactly taboo by the early 00’s, but maybe which the mainstream media weren’t quite used to having brought up frequently and abruptly.

It’s by no means universally acknowledged that Kumi was anything like ‘the last idol’, but she had the fortune to end her mainstream tour of duty when the predominant form of publicity was still billboard advertising and the predominant form of listening to music was still on (bought or rented) CD. I’m assuming that people who have studied media marketing more diligently that me, can explain when that epoch finished, but I feel as though it should have begun to finish in 2007, and that its decommissioning was complete by 2013. And it’s for this reason that I can’t help but think of Girlie Techno as – not so much a footnote or elegy for a means of production that was threatening to become outdated – but a singular vision of a culture that had, in all likelihood, already ended.

How fitting, then, that Girlie Techno puts front and centre one issue of human culture and one issue of gender politics simply by existing and without needing to address it within the context of the songs at all. The final statement of Situationism: What use for the message when it’s no longer even disputable, less still a French Freemasonic Secret, that the Medium Is The Message? What use for the spectacle-as-a-spectacle when society and spectacle are interchangeable, and that fact is neither questioned or plausibly deniable? (I’m assuming that it’s equally unnecessary to elucidate what medium and what spectacle are under discussion here, but instead present a candidate for entry in the small lexicon of Hauntographic keywords: a spectacle which has taken on an undead existance, and which keeps coming back, resilient to exorcism, is a Spectreacle, is it not? And a medium which communicates with the Spectracle, which watching and leering at all of us is more properly….a Clairvoyeurant?)

Now would be a good time to decompress some of that….

Within the narrative of speculative fiction, a good many of the anxieties of felt by human beings about post-human sentience are articulated in the film ‘Blade Runner’. Roughly central to this angst is: what does it mean for humanity if androids are capable of more empathy, love and understanding than actual flesh-and-blood people? In criticism and appreciation of the film, far, far too much energy is wasted on excessively literal attempts to understand ‘whether or not Deckard is a Replicant’, which it’s long been obvious that this question in itself is meant to make us look in the wrong place. The question is brought to our attention by a futureified version of a Hard Boiled Cop, which is used a shorthand not for a bit of meaningless ’50’s drag but for the longer sentence that we’re meant to read Gaff as a character soaked in blood, compromise, mistrust, cynicism and misdirection (hard-boiled cops are expert misdirectors: they misdirect their marks, their informants, their superiors and their own friends. There’s a good reason they’re often in the company of stage magicians, showgirls and artists – people who sell illusion for a living). Secondly, the question is only ever important if too much emphasis is placed on the sexist caricature of Deckard himself – who makes sense and ceases to be a sexist caricature if we understand him to be something other than the main character. Simply deciding not to step into the bear-traps of race and gender politics that the film leaves out for us, we can understand that the question is not “is Deckard an Android?” but “is Rachel human?” which is a far more rewarding question to ask. The character whose name is in the title of the movie isn’t necessarily the main character.

(If Deckard is a robot, the story ends there. Great, fine. A robot Passed for a human for a little while, and fooled a bunch of people who were willing to be fooled as long as their pet Blade Runner did his job. I don’t think, throughout human history, that the existence of sell-outs, traitors, Uncle Toms and collaborators has ever been seriously denied, has it? But it’s a MUCH less interesting conclusion or post-movie pub conversation than the alternative…)

Mimetically, the Los Angeles of the movie is based on a very real place; the four or so city block bounded by Dotonbori and Soemoncho to north and south, and the Nampabashi and Nipponbashi to east and west, which retained their feeling of being part of a futuristic madhouse with no regulation of any excess at all, well after the year 2000. The appearance of absence of regulation derives, of course, from the fact that it’s a little playpen located within a very large and very well-regulated city, but Ridley Scott’s vision of a future dystopia in which decaying structures are augmented with bolt-ons, and normal infrastructure such as wiring, plumbing and ventilation are on the outside of buildings instead of the inside (the architecture of the inside-out was a marked feature of the body-horror of Clive Barker at about the same time) was evident; as was the street-level trade in electronics spares, cheap food and flesh. The joke here of course is that an evening on Dotonbori was one of the most enjoyable times anyone could have wished for, and as far from a dystopia as could be imagined. In short, it made living in the world of Blade Runner look like fun, and the idea that you might be standing next to an android seem like a nonthreatening outcome. It’s perfectly reasonable that ‘androids who look like people’ / ‘people who look like androids’ may have itself been an influence on the brightly-coloured purposefully-synthetic-looking wigs, panstick makeup and high-shine wet-look vinyl affected by imaginative teenage girls for a while, and here, it’s tempting to remind oneself of the Guardian review of ‘Star Trek: First Contact’ which suggested that digital culture may in time breed a class of people for whom Borg Assimilation would be more of an ambition than a threat.

Fig.1. Not as terrifying as the animatronic clown

It is, therefore, possible to understand that the gender politics of ‘Blade Runner’ do not have to be understood in terms of being a piece of misogynist fascist-apologia which may as well starred Charles Bronson and been directed by Micheal Winner, in which a big tough man wastes stroppy hags who get ideas above their station. There just has to be more to it than that. And the more-to-it is of course, that it’s the women who are the main characters, and that whatever their component parts happen to be, those women have more desire, libidinality, joi de vivre and – in any meaningful term – humanity – than the actual human beings. And it is also demonstrable that the digenic politics of ‘Blade Runner’ were both an inspiration for and and inspiration to a real, existing place.

Which doesn’t exactly bring us to Girlie Techno…..quite yet….but a little closer.

It’s a bold and possibly foolish move to try to make a redemptive reading of a pop culture movment which, superficially at least, has at its centre, a spectacle involving dehumanised robot girlies who look suspiciously like Coppelia-Galatea manipulated-by-men dolls (it’s worth recalling what a mistaken reading of Koda Kumi that angle turned out to be.), but what it is hoped can be presented here is that not only is the Coppelia-Galatea archetype overdue some redemption, but that the digenic discrimination between robots/people is an artefact of class discrimination in its own right. And also that Girlie Techno is fantastic.

Sooner or later, nomatter how much personal attachment we have to, it’s going to be necessary to write up Cyberpunk as a failed experiment, either a brave attempt at exploring the unknown, or a self-defeating piece of self-delusion that didn’t so much have seeds of its own destruction embedded within it as was born wrong. Let’s get this straight: I love ‘Neuromancer’ and ‘Snow Crash’ and ‘Body of Glass’ are two of my favourite books ever. I hated ‘The Matrix’ and never saw the sequels. The general aestetics of Cyberpunk, I found dull and re-heated even when they were new, and the fact that Neal Stevenson can write historical fiction that’s almost as good and imaginative as his science-fiction just shows that the great artefacts of Cyberpunk were merely great artefacts, on account of them having interesting plots, interesting settings and characters you care about. Douglas Rushkoff (whom I have the greatest respect for), writing in (where else) Wired magazine, sums up Cyberpunk thusly:

The early cyberpunk idea was that networked computers would let us do our work at home, as freelancers, and then transact directly with peers over networks. Digital technology would create tremendous slack, allow us to apply its asynchronous, decentralized qualities to our own work and lives.

Instead of working for someone – as we had been doing since the dawn of the Industrial Age – we would be freed from the time-is-money rat race and get to be makers. [1]

It took me a while to parse the full implications of this the first time I read it. Really?? Cyberpunk was all about (doing)”our work at home, as freelancers”?? are you serious? Where the hell did I ever get the idea that Cyberpunk was supposed to be interacting with The Urban as on organic unit in an organic unit? Was I mistaken in assuming that Cyberpunk was an extension of Marx’ statement that (Capitalism) “…has created enormous cities, has greatly increased the urban population as compared with the rural, and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life….”. And that part about ‘get to be makers’? You mean, making stuff? Like hobbyists and old ladies in knitting circles do all the time? Could someone please explain how the sub-fusc of Cyberpunk is in any way a prerequisite for this?

The problem is that the Rushkoffian definition of Cyberpunk (and Rushkoff is being unfairly singled out here – he is by very far the only thinker that has put forward this rationale) is adolescent in the extreme. It reduces to a very, very understandable but hardly sustainable idea that One should be Paid to be Cool and Brilliant. Of course, that economy came to pass. In 2018, people actually can make a living by being cool, except they’re people like Bella Hadid and not people like Marge Piercey. More troublingly, the concept of being-paid-to-be-brilliant is inescapably Wired-in (oh, look at me, I tried to be funny again) to the commodification of ideas, the idea that the outcome of ones’ brilliance is Intellectual Property, which means it’s Property, which means….making a living from Owning stuff, which is Capitalism. And be sure the have wordes for laying at hande at all times, because the very, very unbeloved spectre of subscription-model Objectivist Utopianism is about to pop out of the wall, asking to borrow some money until its next get-rich-quick pyramid-sales scheme hits big, big paydirt, and if you find yourself thinking of Andrew Galambo here, you’re not the only one. There is a ghastly irony in the fact that the very economy envisioned and planned by the early Cyberpunks – to reiterate – being Cool for a Living – did truly come to life, but I doubt that Influencer Culture was what the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit had in mind. But the most ghastly irony of all is the extent to which certain CCRU alumni have become involved in modern hate movements. The misanthropic and elitist aspects of Cyberpunk were close enough to irony to be considered as irony, but it’s enough to say that some of that ironically-appropriated fascist imagery doesn’t look remotely ironic nowadays.

The parts of The Future that Cyberpunk never seemed to figure out was what Youth Culture would look like in the future. ‘Snow Crash’ is a practically faultless work of Picaresque adventure-fiction, one which re-enforces and is re-enforced by its (unintentional?) companion-piece ‘King of the Vagabonds’, but having set out its stall as the story of a twenty-eight year old man who is already badly generation-gapped by youth culture, then ill-advisedly attempts to show us what Youth Culture looks like. To the book’s credit, it seems to realise how ill-advised this step it, and withdraws from it as rapidly as possible, but the fact is that Cyberpunk never did this kind of thing very well. It turned out that a generation of youth, never having known life without The Internet, had very little interest in forming violent street gangs (the violent street gangs are, as ever, comprised of poor kids from subhumanly deprived backgrounds, and their tribal and inter-tribal behaviour is not anthropologically different from the behaviour of violent gangs at any time in the last three thousand years) and getting shark-tooth implants and stealing tech from mega-corporations. Stevenson succeeds when he shows us One teenage girl, who is already flagged as an outlier and eccentric within her own outlier/eccentric subculture, but falls to bits completely when he tries to show the subculture at large (the future is Ska-Metal for Skaters? Is that the best we can do?). This wouldn’t be so problematic if the full-time, professional, cool-thinkers-for-a-living who were the self-identified backbone of cyberpunk culture did a much, much better job of the same thing….

But here’s the thing….

I’ve struggled for the better part of a year now with Burial. I’ve listened many, many times to the album which so many modernist-minded critics and cultural commentators found so evocative and zeitgeistisch, and – I am more than willing to accept that this is my problem and no-one else’s, and I don’t get it. I read the interviews with Burial, and the guy acquits himself wonderfully. I was desperate to hear the album that apparently owed so much to M.R.James; urban myths and after-hours lock-in ghost stories; pointless walks to dismal places and haunted shortwave radio; but that wasn’t the album I ended up listening to. I’ve tried to listen to it in every mood I have happened to experience; in every location that might seem evocative and at many different times of the day and night, and I can neither mine anything out of it, nor can I allow it to work on me in any meaningful way. One album wouldn’t necessarily be problematic, but I’ve had similar lack of success with approaching almost all of the hallmark signifiers of Cyberpunk Modernism. I enjoyed the journalism on Jungle and Hardkore, but I couldn’t get within a country mile of actually getting ‘Timeless’, and it becomes somewhat anxiety-inducing to approach a work, recommended by critics you trust – whose advice has served you well in the past – and find yourself quite earnestly, months or years and repeated attempts later, utterly defeated.

In the end, however much residual affection I have for Gibson, Stevenson and Scott, the only thing that can really be done with them in the context of Cyberpunk is to attempt to separate them from the quicksand of a milieu which has proved not merely politically toxic, but terribly harmful to the mental health of the people who’ve become involved in it (this is not a long distance from disengaging the gains made during the regency of Neoliberaism from those gains being dependent on Neoliberalism, as we tried to do with City Pop.) You shouldn’t have to eat your Fascist meat-and-potatoes before you can your scrummy spec-fic pudding.

It should be recalled that we set out here to locate Girlie Techno far and apart from the ugly, self-regarding / self defeating (self)-hate culture that Cyberpunk didn’t start off as, but became. In the nomenclature of Distributed Version Control, Girlie Techno is a branch or fork of Cyberpunk culture which wasn’t the form (self)-determined to turn into an autophobic, biophobic, gynophobic iteration of depressive sadomasochism; in short, it was the fork which got the flesh, pheromones, fun and feeling, and not the phobos.

Fig.2. Unknown Singer, 2009. The vocoder makes the vocals sound more human.

Fans of television programmes like ‘Doctor Who’ and ‘The Avengers’ are very familiar with Cybermen and Cybernauts and many other kinds of biophobic body-horror androids, and it’s hardly new or radical to suggest that creatures like these can be understood in terms of depression and proletarian enervation. Both kinds of creature are shown in roles associated with either lower-working-class drudgery or Gramscian white-collar proletarian stress-and-anxiety (the outcome of the stress and anxiety is inevitably systems failure). The classic image of the Cybernaut is in its disguise – a trenchcoat, trilby hat and tie – which is not merely the sinister juxtaposition of the familiar with the uncanny, but a perfect summing-up of the Dumb Prole, stuffed into a cheap, badly-fitting suit and oversized shoes, and tricked into thinking he’s been given entrance to the Middle Classes, except that his new Salary is less than his old Wages. He reacts with rage, only ever rage, butchering every bourgeois that crosses his path, and eventually begins a self-defeating fight-to-the-death with the Skilled-Worker Cybernaut (signified by his overalls, flat cap and box of precision tools). Divide and rule, the white-collar and blue-collar proletariat at each others’ throats. In their most iconic appearance, Cybermen appear in actual sewers, with all the connotations that go along with them: the coarsest, most unhygenic aspect of public-sector labour; of a literally underground threat. We are told that Cybermen were ‘once’ human beings who have undergone some process (A religious enlightenment? Surgery? Therapy?) to remove their ’emotions’. Of course, to un-modified human beings who understand what depression is like, being unable to Feel is not so much a threat as a promise or an opportunity. Who hasn’t contemplated, sometime, taking some action to Make The Bad Emotions Go Away. The word ‘Robot’ is derived from the Czech for ‘manual worker’, and it’s hardly surprising that the end-point of Cyberpunk culture (the people who thought they should be able to Be Cool for a living) was to despise labour, and labourers, and why that whole fork ended up its members dead, brain-dead or depressed.

Fig.3. Unknown Singer, 2008. What is real, what is maufactured? Humans never have hair, skin and teeth that perfect.

Girlie Techno is the alternate fork, the parts deemed worthless, and subject to removal by the Cybernauts, Cybermen and Cyberpunks. When we over-alliterated earlier on, and suggested that it was the fork that became the custodian / beneficiary of the flesh, pheromones, fun and feeling, we omitted of course to say the feminine. And as was stated at the beginning, we’re interested chiefly in Rachel here and not Deckard (for those of you who think that Roy Batty’s breaking of Deckard’s two fingers, after which he can’t use his gun properly, is some sort of metaphor for castration, please remember that e-masculation is a masculine privilege), we’re not interested in the implications of “what-if the person is really an android?” because that’s boring, and we already have the answer: he’s only what he was before. A defeated, depressed process worker dressed up as human, just like the Cybernaut-in-a-suit battering down a rich guy’s front door like a demented encyclopedia sales man who is not going to have the door slammed in his face this time

Fig.4. Kozue, 2007

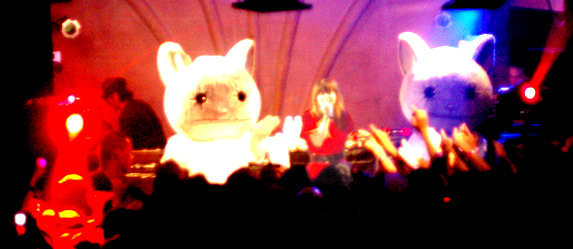

Fig.5. MEG, with Kuma One and Kuma Two, 2007

— Cyberpunk turned out to be a massive letdown, fulfilling not even one of its promises.

–“Coppelia does nothing but sit and read”

–“they are only ever shown as passive recipients of the Gaze. They are never shown dancing”

–The girlies of Girly Techno do almost nothing but sing and dance.

Girlie Techno retired itself when there were no more memories, never to be part of the spectracle. Indulge me this once. All those moments, all those memories, will be lost like tears in the rain.

*the question I haven’t even begun to address here is not “is it possible that this subject has been covered in some artefact of Japanese animation?” but rather “what several dozen artefacts of Japanese animation that I don’t know about have covered this subject”

** MOSTLY Dotonbori and Soemoncho. About every ten yards between Sennichi-mae and Sakaisuji-Hommachi there’s a bit of street signage or architechture that reminds you of something from ‘Blade Runner’ – the double-sliding-door set where Joanna Cassidy’s character is shot is a sound-stage recreation of (I think) Number 5 entrance of Semba Chuo, the vast wholesale textiles market that runs under Route-13, for instance. The iconic symbols of Dotonbori used to be a somewhat-nightmarish crab automoton, and on the opposite side of the street, an utterly nightmarish robot clown which gave me almost as many nightmares as the cackling automaton that used to live in the entrance hall of Blackpool Tower. I actually expected to see an iteration of this animatronic laxative in Sebastian’s workshop somewhere. In any case, the native folk seemed greatly flattered by Scott’s attentions, and copied THE HELL out of Sean Young’s loose perm and Daryl Hannah’s Dandy Highwayman makeup; and, bless him, Scott re-repaid the favour by using the locations as actually locations in ‘Black Rain’ seven years later.

***Ridley Scott is from South Shields, and would have been making ‘Alien’ and ‘Blade Runner’ at the time that the Yorkshire Ripper murders were taking place. This was also before the killer was identified as being from Leeds, and was assumed to be from Tyneside due to the exaggerated importance placed on the (fake) ‘Geordie Ripper’ telephone calls. It’s absolutely unthinkable that Scott would have set out to make a film in which an inhuman killer murders (amongst others) a prostitute and a nurse***, with the full approval of the police and intend it to have been taken at face value.

****possibly this is a stretch. Roy Batty’s profile describes his ‘function’ as ‘Colony Defence’, which I’m assuming will include some Combat Medic skills since we assume he’ll be fighting alongside human colonists.

*****For advocates of capitalism as a systems of ethics and economics, it’s worth pointing out that Influencer Culture came close to producing the sort of gleeful revenge fantasy that fourteen-year-old Cyberpunks with too much Alan Moore and Killing Joke on their shelves can only dream of….if, indeed, they had the scope of imagination to dream of it at all. In 2017, Billy McFarland and Ja Rule staged the actual abduction of 500 rich, spoiled, obnoxious children to a Caribbean island where they were almost forced to fight each other for food, water, shelter and repatriation. This proves that no matter how well-written and insightful ‘The Hunger Games’, ‘Battle Royal’ and ‘Lord of the Flies’ were, Capitalism can do anything better, and, true to its own ethics, do it without state coercion. And get people to pay for it. And then see to it that the only people who ever actually get rich and stay free are the con-artists and the lawyers. Ja Rule later started another business called Iconn. You couldn’t write jokes that good.

****** Nick Land has written a book called, unbelievably, “Dragon Tales: Glimpses of Chinese Culture”, which is the kind of title that was being invented approximately twenty years ago to mock the tendency of far too many visitors to for too many East Asian countries to feel the need to write a book ‘lifting the lid’ on the ‘hidden world’ that lay ‘just beyond what the tourists are allowed to see’. Some of the little books that parodied this tendency were genuinely hilarious, and expertly poked holes in a real, existing Journalistic tendency to White Supremacy and Yellow Peril-ism. What’s not remotely hilarious is that Land is an actual, existing White Supremacist who is currently mired in one of the most laughable excuses for a Readers’ Digest version of a bad copy of an underthought example of psueudophilosophy since Objectivism.

[1]https://www.wired.com/2013/04/present-shock-rushkoff-r-u-sirius/